Why making public transport free is a bad idea

The short answer would be: because it is not free. But let’s elaborate on that.

The mayor of Paris, Ms. Anne Hidalgo, recently announced plans for a study of free city-wide transport. The goal is to develop clean mobility and boost air quality by reducing the number of cars on the roads, which would require making public transport more attractive.

That reasoning is appealing but happens to hold some misconceptions.

First, the city of Paris isn’t in charge of the transport system. It is actually the Île-de-France region through the regional transport authority, Île-de-France Mobilités (the local equivalent of London’s TFL, which I happen to work for). Ms. Hidalgo knows it and it is obviously more of a political move, but it shouldn’t overcloud the question: would free public transport help reduce the number of cars on the roads?

The major problem with free public transport is that it creates the perception of a no-cost service. Just as car drivers commonly assume that there is no cost involved in driving their car somewhere. The catch of the car-based system is that the car trip is not in fact free — one should at least include gas, parking space, insurance and depreciation costs, even if environmental cost could also be part of the equation.

Likewise, this perception of freedom is important for public transport, which is far more environmentally and resource efficient than own-car travel. It means in this case that full access to the system doesn’t need to be literally free for its users but that, from a financial perspective, it becomes front-loaded and affordable. Still, any public service needs money. In most European cities that offer public transport, users can get a monthly or annual transit pass that opens up the public system to unlimited use. Now, how they pay and how much will be part of the overall political/economic package of their community is decided by the local transport authority. In cities that offer such passes — as is the case in most cities in France — the remainder of the funds needed to pay for these services comes from other sources: employers and local governments.

In Paris, the Navigo annual travel pass gives you unlimited use of the public transport networks every day for 75,20€ a month. Moreover, at least 50% of the cost of your travel pass can be reimbursed by your employer. This makes the Navigo pass one of the cheapest in Europe, even though it also offers one of the most extensive networks.

How much does a monthly transit pass cost in major European cities? — numbers in 2016 (source)

The fares paid by passengers don’t cover the costs of operating transport services: they indeed represent less than 30%. The rest is funded by employers (mostly transport tax) and local governments.

Ile-de-France Mobilités sources of income in 2016 (source).

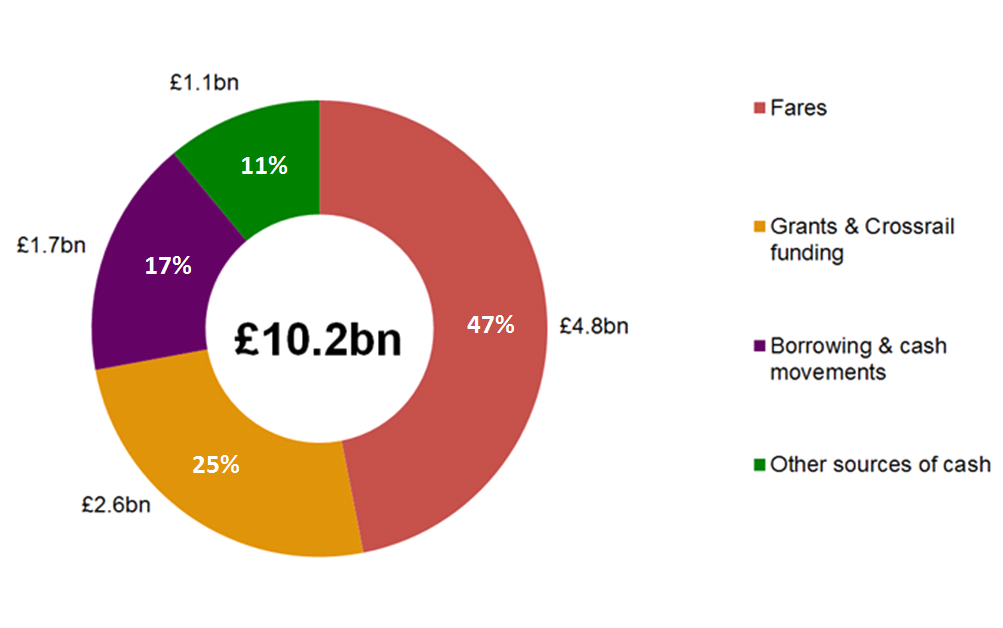

In London, where the equivalent annual transit pass is a lot more expensive (£295 or around 410€ a month), it is however the largest source of income, representing almost half of the sources of cash.

TfL sources of cash 2017/18 (source)

In short, transportation in Paris is already cheap and passengers only pay a small part of the costs, so fares are not what prevents car drivers from taking public transport instead. This was clearly demonstrated in December 2016, when Paris was suffering its worst and most prolonged winter pollution wave in at least 10 years. To battle this air pollution peak, due to the combination of emissions from vehicles and domestic wood fires as well as near windless conditions, Parisians could use public transport for free and car traffic was restricted. After 4 days of free public transport, the number of passengers increased only by 5%. In fact, the Paris public transport system currently stands on the verge of saturation.

To tackle overcrowding and offer a more reliable and comfortable service, massive investments have been voted: upgrade of suburban railways, expansion of metro lines (1, 4, 11, 12 and 14), building of new tramway lines and purchase of new rolling stock. Moreover, Grand Paris Express is bringing 4 additional automatic metro lines, which makes it the largest transport project in Europe. So now is not the time to reduce funding, as you can see in this forecast of funding needs until 2030.

Ile-de-France Mobilités funding needs between 2018 and 2030 in M€ (source)

Funding needs are expected to be multiplied by 18 between now and 2030, because extending the network means operating a larger transit system. It is actually a challenge to figure out how to pay for it and balance public accounts — this could actually be the subject of another story! So lowering fares is highly unlikely in the recent future to say the least. A committee of experts has been designated to write a report, due in september, on free public transport, fundings and pricing policies, and we’ll see if they draw the same conclusion.

When all is said and done, even if free public transport is not the way, this doesn’t mean there is nothing to be done. Indeed, we should support any initiative aiming at reducing air pollution and the scope is wide: improve public transport experience, promote car-sharing, encourage biking, develop Zero-Emission Vehicles (ZEV) — meaning electric cars obviously, but also electric motorcycles and scooters. The point is to widen eco-friendly and ressource efficient options, so that anyone can choose the most appropriate means of transportation for their journey. This is where it needs to get innovative and, in my opinion, exciting!

Bibliography: